A simple way to identify natural human rights is to ask the question, “Can this creature do so and so? If the answer is yes, then the natural right is obvious. If he can do it, he has the agency, the authority, the power, and therefore the right to do it.

A simple way to identify natural human rights is to ask the question, “Can this creature do so and so? If the answer is yes, then the natural right is obvious. If he can do it, he has the agency, the authority, the power, and therefore the right to do it.

That’s an easy and powerful way to discover a candidate right. But we also need to ask “Can he do that without injuring someone else?” If the answer is “No”, then there is a problem. So some rights are reduced or lost during their usage. How much rubbish can you burn under your neighbor’s window before you violate his rights?

The word “rights” occurs very frequently but the sources of those rights are very rarely explained. Most authors seem to use the word to justify anything that sounds good. We hear a lot of talk about rights to “equal wages”, or even “decent wages”, and of “social justice”. We even hear of “freedom from” this or that. These are abstract rights and not natural rights, so we may question whether they are really rights at all. Perhaps they are just wishful thinking or an attempt at persuasion.

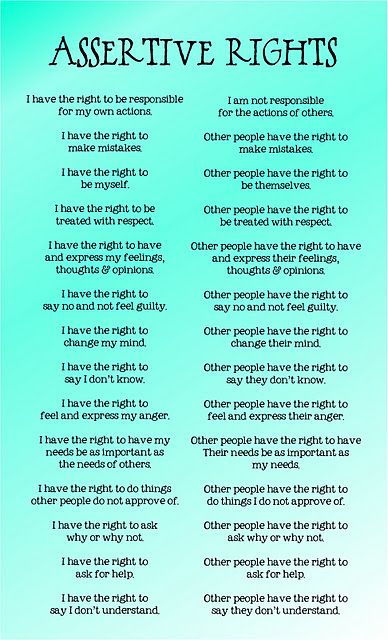

This list of so-called Assertive Rights I found on Pinterest is a good example of popular use of the word “rights”. They all seem to be natural human rights.

Citizen Jim’s Human Rights

James was the most common boy’s name during the past century, so I’ll use Jim to represent all citizens. Jim has all the rights, powers and authorities of the rock, the tree and the beaver plus more.

Jim has the ability to reason, to choose how to react to his circumstances, and to invent, imagine and believe. So he has rights of the mind and heart. These are also inalienable, immutable and inherent. As with all rights, Jim must have the authority to exercise his powers or abilities to their maximum. By doing that he can enlarge those powers and rights. He can grow.

Of all the human rights, this one needs special notice. Our civilization can only grow better as its individuals grow better. Laws based on the abstract concept of “the good of society” need to be re-examined to assure they do not forget the individual citizen. In their anxiety to improve the general welfare, legislators too often write laws that fail to examine their effect on Jim. The result of that mistake is often laws that destroy rights, discourage growth, and even encourage Jim to be dishonest.

Rights of Conscience

Jim has an inner voice we often call the “conscience”. It helps him use his rights in a way that honors the rights of others. This right is especially valuable to Jim when he associates with other creatures. Some philosophers deny the idea of a conscience. Ayn Rand, for example, says “Since man has no automatic knowledge, he can have no automatic values; since he has no innate ideas, he can have no innate value judgments.”1 However, having raised ten children, my experience tells me we are born with a conscience. I may decide to prove Ayn wrong in a later post. I have hard evidence. But I digress.

Jim has an inner voice we often call the “conscience”. It helps him use his rights in a way that honors the rights of others. This right is especially valuable to Jim when he associates with other creatures. Some philosophers deny the idea of a conscience. Ayn Rand, for example, says “Since man has no automatic knowledge, he can have no automatic values; since he has no innate ideas, he can have no innate value judgments.”1 However, having raised ten children, my experience tells me we are born with a conscience. I may decide to prove Ayn wrong in a later post. I have hard evidence. But I digress.

The right of conscience was the top priority in the minds of the founders. They agreed that freedom of conscience was the only safe harbor for all freedoms and that an active conscience in each citizen was the only hope for a long-lasting government. History told them, and us, that evil is the enemy of freedom. The fundamental principle is that self-discipline is far superior to law enforcement. It’s a no-brainer.

Jim’s Conscience and the First Amendment

To protect Jim’s right of conscience, the first amendment to the US Constitution prohibits the establishment of any religion or philosophy of life. It also guarantees Jim’s freedom to live according to his personal worldview. The first amendment does not say that religious symbols must be kept out of the public square. Such an idea is inherently impossible to achieve as we shall see as this book unfolds.

Protecting Jim’s conscience means that Jim needs to free of any philosophical or religious coercion such as threats to his welfare, circumstances or other freedoms. He also needs free access to unfiltered information – an education that treats all religions or worldviews or philosophies, or whatever you prefer to call them, with equal respect and without bias. This means that religions, philosophies, and worldviews need to be taught in Jim’s schools but in an unbiased and respectful manner.

Note that when the United States government has any influence upon the curricula and methods of instruction in our schools, it is dangerously close to being able to establish a religion. In fact, many citizens think that the US Department of Education has already “weaponized” our schools as atheist seminaries. What do you think?

Note that when the United States government has any influence upon the curricula and methods of instruction in our schools, it is dangerously close to being able to establish a religion. In fact, many citizens think that the US Department of Education has already “weaponized” our schools as atheist seminaries. What do you think?

The Limits of Jim’s Rights

So whatever Jim can do he has the right to do. But we need to talk about the boundaries of those rights. This is the most interesting and instructive part of the study of human rights. As a physicist, I learned that boundary layers are where the action is.

[edsanimate_start entry_animation_type= “” entry_delay= “” entry_duration= “” entry_timing= “” exit_animation_type= “slideOutLeft” exit_delay= “0” exit_duration= “2” exit_timing= “linear” animation_repeat= “1” keep= “yes” animate_on= “hover” scroll_offset= “” custom_css_class= “display-right-inline”] [edsanimate_end]

[edsanimate_end]

That layer where pure gasoline fumes meet the air is where the action can be, and if there is a problem, it will arise there first. You can snap a spark in the air near the gasoline fumes and nothing will happen, you can snap a spark within pure (no air) gasoline fumes and nothing will happen because there is no oxygen there. (Please don’t try this!!) The danger lies where the two contact one another – the boundary layer.

In a similar fashion, Jim and his neighbor can exercise their rights without concern up to the point where those rights begin to touch one another. This is true for Jim and for nations.

Both our revolutionary war and the establishment of our democratic republic happened in this boundary layer. The rights of the British, embodied in King George III, were in grave contact with the rights of the Americans. Simultaneously, the rights of the Americans were being gathered up in a great cooperative that finally created the US Constitution. It is interesting to notice that when people refuse to cooperate the boundary layer gets activated with conflict. When people refuse to fight, the boundary layer gets activated with contracts. Our founding documents are the contracts between Jim and his government.

Thomas Jefferson commented on religious freedom with these words: “The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”2 This is a good test for Jim to use whenever he wonders about any conflict between his human rights and his neighbor’s.

Good Laws, Bad Laws, and Human Rights

If Jim’s exercise of his rights does damage to his neighbor, then Jim needs to restrain himself. We have millions of pages of laws because people are not as good as they ought to be. So what defines “good”? That question is easier to answer than might be suspected – at least in the area of government and laws. What is good is simply what recognizes and honors rights. Laws that infringe rights or that cause Jim to infringe his neighbor’s rights are not good laws. This is not rocket science. A bad law infringes rights without proper justification.

If Jim’s exercise of his rights does damage to his neighbor, then Jim needs to restrain himself. We have millions of pages of laws because people are not as good as they ought to be. So what defines “good”? That question is easier to answer than might be suspected – at least in the area of government and laws. What is good is simply what recognizes and honors rights. Laws that infringe rights or that cause Jim to infringe his neighbor’s rights are not good laws. This is not rocket science. A bad law infringes rights without proper justification.

However, thousands of pages of laws have been written that do not protect rights as they should. There are two ways bad laws violate Jim’s rights: 1) they define (and therefore create) a class of people apart from the citizenry in general, and award or restrict those people, or 2) they give government powers to do things that would subject Jim to punishment.

The next post will deal with these bad laws in more detail, including the common but dangerous idea that some people’s rights are superior to Jim’s.

1 Rand, Ayn. The Objectivist Ethics. Nathaniel Branden Institute, 1961.

2 Jefferson, Thomas. Query XVII, Notes of the State of Virginia, 1783.