There is a space between words and their meaning:

Poets and politicians frolic in that space.

Poets and politicians frolic in that space.

Puns reveal it.

Truth seekers explore it with reverent interest.

Bigotry and hate corrupt it.

Evil abuses it.

Love cherishes it.

Librarians worry about it.

Lexicographers live on it.

Lazy thinkers crash and burn in it.

As humans, our minds give us a space between stimulus and response and that gives us the power to choose how we will act. In this case, the stimulus is a word and the meaning it brings to mind is the response. It is interesting to notice that these “meaning” responses are often quite fuzzy. Concrete things, like a spoon, for example, give us a pretty clear idea of the meaning of the word. Conceptual words like “friendship” give us a whole cloud of meanings – all closely related, but not nearly so clear as a spoon.

Peace, understanding, and love come from careful attention to this space between words and meanings. Contention, misunderstanding and hard feelings come from ignorance or deliberate abuse of it. We see this today in our beloved nation. But, there is a natural cycle to such things: the more the pendulum swings in one direction, the greater the force to move it back the other way. We went through this sort of thing in the 1790s. So there is hope that today’s war of words will result in calmer minds, clearer thinking, and new progress. But let’s look at this space closely and see what we can learn.

The Nature of The Space

The ability to separate words and their meanings is part of communication. It is something that we rarely think about, but if we don’t, we may think we know something that we don’t. Or we may think we are communicating when we aren’t. We all have trouble talking with someone who uses words differently than we do.

But on the other hand, poetry is only possible because words and their meanings are connected by a sort of “mental culture”. That culture exists because of the shades of meaning that come to mind as we use the words. But back to the first hand, we have to use words to communicate. It’s another dilemma in our interesting world.

So one of the problems with the space between words and meanings is that it allows meanings to drift. Noah Webster worried about that and spent many years to became the world’s most famous lexicographer. He published his first dictionary in 1806: A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. He immediately went to work on a much larger dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language that he published in 1828. It defined about 70,000 words: 17% of them published for the first time.

Noah Webster’s Work

Webster learned 28 languages and studied the ancient origins of words so he could understand this space. He believed it was very difficult to have political discussions and worried especially about abstractions. He tried hard to introduce an attitude of precision towards words and their meanings. He was convinced that imprecision was the source of a lot of trouble.

“[Webster] was most distressed by the insertion of terms like “the people,” “democracy,” and “equality” into the public debate, complaining that such words were “metaphysical abstractions that either have no meaning, or at least none that mere mortals can comprehend.” … Webster argued that it was impossible to have a meaningful discussion about politics in America, because the language used by spokesmen on all sides of a controversy had become hopelessly convoluted.1

In his book, After the Revolution: Profiles of Early American Culture, Joseph J. Ellis talks about the political dialog of the time —

Virtually every historian who has studied the political history of America in the 1790s has noted the frantic, crisis-ridden tone of the public debate that Webster was entering. … One finds [George] Washington, the most revered of the founders, described as “treacherous in private friendship, and a hypocrite in public life” and the wellspring of “political iniquity and … legalized corruption.” Adams, Hamilton, and Jefferson received the same treatment, or worse. Webster found himself labeled “Domine Syntox,” “a pusillanimous, half-begotten, self-dubbed patriot,” “an incurable lunatic,” and “a deceitful newsmonger … Pedagogue and Quack.”

No real dialogue was possible for there no longer existed the toleration of difference that debate requires. The mutual suspicions, supercharged rhetoric, and exaggerated accusations are important to recognize, in part because they confounded Webster and eventually drove him out of public life, [and] in part because they reflected the widespread apprehension about the stability of the infant republic and the future direction of the new nation.2

So What is the Real Problem Here?

As our culture becomes more and more polarized by political issues, it becomes important for us to fully understand one another, especially across that divide. This space we are talking about, facilitates the lack of understanding that troubles us. And worse, more and more citizens seem to use it to cast verbal stones at one another. And sometimes those stones are real.

Our elections have become more and more a referendum on religious preferences that are reflections of a parallel struggle between liberal and conservative thought. Near the root of all this ideological turmoil is the idea that we need to separate religion and government.

Meanwhile, that separation can never be accomplished. Yet our culture is investing a tremendous amount of legal and emotional energy in this unspoken goal. That diverts our efforts into hopeless channels of unnecessary conflict. This impossibility of separation of church and state will be the topic of an upcoming post.

Our Imperfect Language

Because our language is imperfect, it is impossible to be precise about anything but the most physical objects where we can declare dimensions, for example. Other topics have to be discussed with what we have available, and because almost every word has multiple meanings (not to mention inferences, and implications) it is impossible to be precise about the most interesting and vital subjects. So every expression is more or less a metaphor for what we are actually talking about.

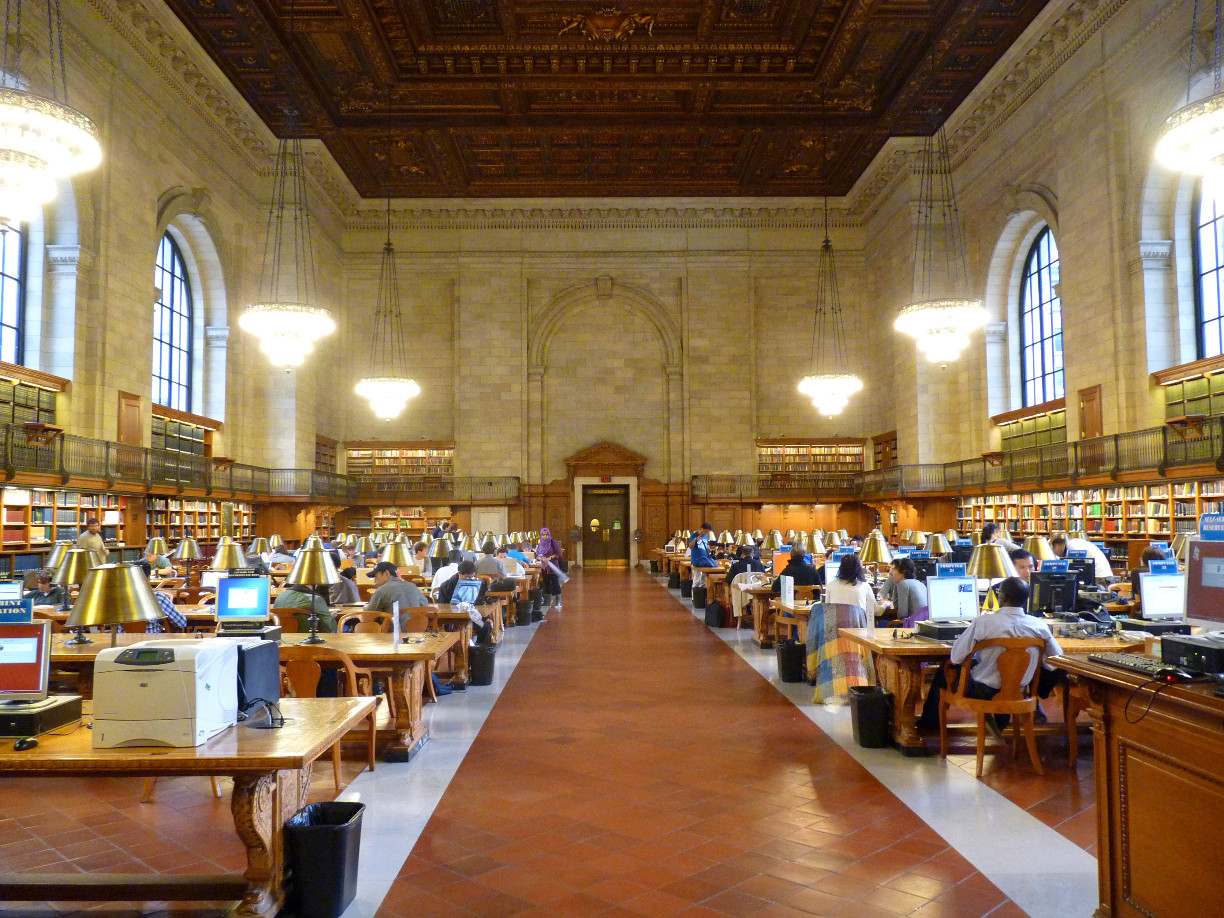

[Author’s note: The featured image is a pile of wet weeds cleared off a field that is in the final stage of spontaneous combustion just before it burst into flame. It seemed a fitting metaphor of the heating up of our popular rhetoric.]

1 After the Revolution: Profiles of Early American Culture, by Joseph J. Ellis, W.W. Norton, 2002, pp. 199–203.

2Ibid.

Example of “space:”

Great question! Gives me a chance to improve this post significantly.

Your comment was a big help in sleuthing this out. You used one word and that made me search my space between words and meanings to try to understand what you were saying.

I am rather certain that it is the same “space” we sometimes talk about between stimulus and response. So in this case, the stimulus is the word and its meaning is the response. As adults learning a new language, we are quite aware of what is happening in our minds as we work to remember the connections between them. Those connections are where we get into trouble. I remember figuring out at a young age that “dawnsearly” was not a word I still hadn’t learned, but two words (in “Oh say can you see, by the dawn’s early light, …”).

I have updated my post to reflect this understanding of the space.